Comfort in HVAC Design: Optimize Indoor Air Quality

Achieving comfort in HVAC design involves balancing temperature, humidity, and airflow. By utilizing metrics like PMV and PPD with CFD-based HVAC simulation, engineers can enhance indoor environments for improved comfort, efficiency, and air quality.

ARTICLES

Wiratama

10/26/20254 min read

What is Comfort in HVAC Design?

Comfort in HVAC design refers to the state in which building occupants feel thermally satisfied – neither too hot nor too cold – while the indoor environment supports health, productivity and well-being. Standards such as ASHRAE 55 define comfort as “that condition of mind that expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment.”

Achieving comfort is more than just setting a thermostat: it requires balancing multiple environmental factors (temperature, humidity, air velocity, mean radiant temperature) and personal or behavioral parameters (metabolic rate, clothing insulation).

Key Parameters That Define Thermal Comfort

Environmental parameters

Air temperature: The dry-bulb temperature of the space.

Mean Radiant Temperature (MRT): The uniform temperature of an imaginary surrounding enclosure that would exchange the same radiant heat with a person as the actual surfaces.

Air velocity: The speed of air movement affects convective heat loss/gain around occupants.

Relative humidity: Impacts evaporative heat loss and perception of warmth or coolness.

Personal parameters

Metabolic rate (met): The rate at which a person produces heat, depending on activity level.

Clothing insulation (Clo): The insulation value of what the occupant is wearing; it affects heat exchange between body and environment.

Together, these parameters define the heat balance between the human body and its surroundings. When heat production equals heat loss (in a steady‐state sense), the occupant is in a “neutral” thermal condition.

Comfort Metrics: PMV & PPD

The most widely used comfort metrics in HVAC design are:

Predicted Mean Vote (PMV): Developed by Fanger, this index predicts the average occupant thermal sensation on a scale from –3 (cold) to +3 (hot).

Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied (PPD): Based on PMV, this metric predicts the percentage of occupants likely to feel dissatisfied with the thermal environment.

As an example: if PMV is 0 (neutral), PPD is around 5% (i.e., even in optimal conditions, about 5% of people may feel dissatisfied). If PMV moves away from 0, PPD rises.

According to ASHRAE 55, acceptable thermal comfort typically implies PMV in the range of about –0.5 to +0.5, which corresponds to PPD of less than ~10%.

Steps to Define Comfort in an HVAC Design Project

Define the occupant profile – Determine the typical activity level (met) and clothing insulation (Clo) for the space.

Define design conditions – Establish target indoor air temperature, humidity, air velocity, and mean radiant temperature for the space.

Use a comfort model – Apply the PMV/PPD model (or adaptive comfort model if applicable) to check whether the combination of environmental and personal parameters yields acceptable comfort levels.

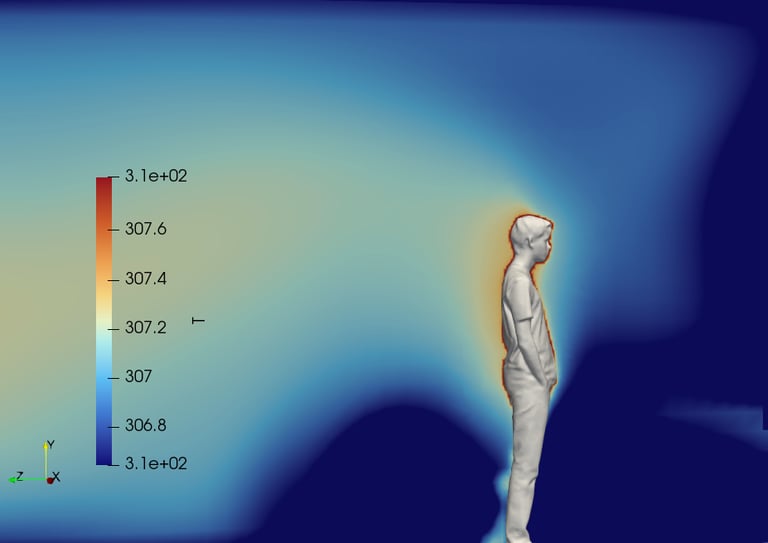

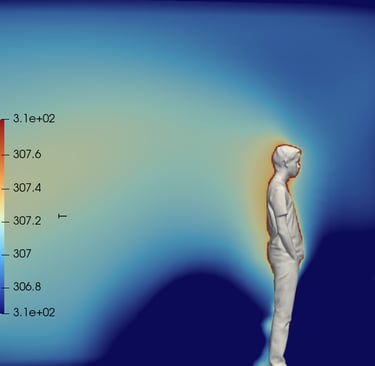

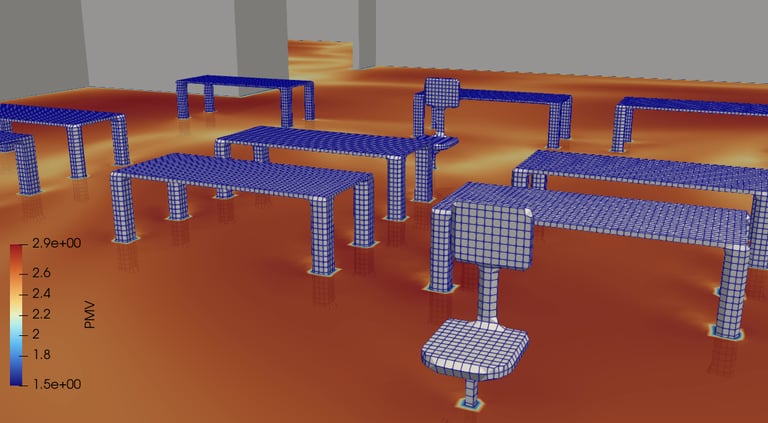

Simulate or evaluate spatial and temporal variation – Real spaces are not uniform. Use tools (e.g., CFD or zonal models) to assess how comfort varies across zones: for example near windows, diffusers, or along occupant paths.

Design HVAC system to meet comfort targets – Specify supply air temperature, velocities, diffuser types/locations, return layouts, radiative surfaces, etc. – such that comfort criteria are met throughout the occupied zone.

Verify and monitor – During commissioning or post-occupancy, measure relevant parameters and review PMV/PPD (or other comfort indices) to ensure performance meets targets.

Challenges & Practical Considerations

Spatial non-uniformity: Temperature or velocity gradients (e.g., floor to ceiling, near glazing) can cause local discomfort even if average conditions are within range. Use detailed modeling to capture these.

Individual variation & adaptation: Occupants differ in their thermal sensation due to age, health, acclimatization, culture and personal preference. Comfort models like PMV represent averaged responses.

Air movement & drafts: Even when temperatures are acceptable, high air velocities or turbulent flows can cause local discomfort (drafts) – this needs to be addressed separately in the comfort design.

Radiant effects: Large surface temperature differences (e.g., cold windows, warm floors) impact MRT and can degrade comfort though air temperature seems acceptable.

Energy/comfort trade-off: Designing strictly for neutral comfort (PMV ≈ 0) may require more energy. Sometimes a slight shift in target (e.g., PMV = +0.3) may yield energy savings while maintaining acceptable comfort.

Dynamic/seasonal conditions: Occupant comfort expectations and behavior may change over seasons; in naturally ventilated or occupant-controlled spaces, adaptive comfort models may be more appropriate than fixed PMV/PPD targets.

Why Comfort Definition Matters in HVAC Design

Defining comfort explicitly means that HVAC systems are designed not just for equipment capacity or airflow rates, but for human-centric performance — ensuring occupants feel comfortable, healthy and productive. Proper comfort definition allows:

More precise HVAC sizing and configuration (avoiding over-cooling or over-heating)

Better occupant satisfaction & productivity

Reduced complaints and rework

More efficient system operation (because comfort targets guide actual performance)

Compliance with standards (e.g., ASHRAE 55) and certifications (e.g., WELL, LEED) that include thermal comfort criteria.

Integrating Comfort Definition with HVAC Simulation Tools

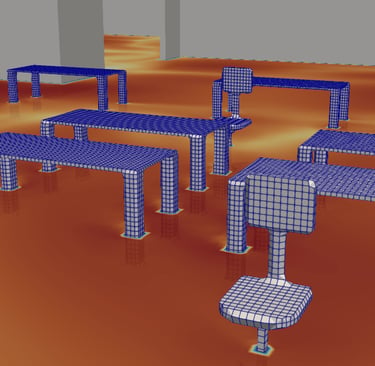

Modern HVAC design increasingly uses simulation tools to verify comfort across the project. Tools that incorporate airflow and thermal modelling (e.g., CFD) allow designers to:

Visualize velocity, temperature and mean radiant temperature distributions

Identify and mitigate zones of discomfort (drafts, dead zones, cold spots)

Calculate comfort indices (PMV, PPD) at multiple occupant locations

Compare alternative HVAC layouts (supply diffuser positions, ventilation strategies, radiant surfaces)

By following a well-defined comfort target and simulating to check compliance, HVAC design becomes performance-driven rather than rule-based.

tensorHVAC-Pro is a flow and thermal HVAC Simulation software dedicated for HVAC engineers, no need to be CFD expert to simulate your problem. Learn more..

Read other articles