How to Improve Thermal Comfort in an Office Environment

How to Improve Thermal Comfort in an Office Environment

ARTICLES

Wiratama

12/4/20253 min read

As global temperatures continue to rise and working hours extend, maintaining comfortable indoor environments has become a central priority in modern building design. Office spaces today contain dense clusters of electronics that generate additional heat, while variations in occupant metabolic rate and clothing create diverse thermal preferences. The result is a familiar struggle: some occupants reach for a sweater while others open a window, all within the same room.

Thermal comfort in workplaces is not just a matter of convenience. Research shows direct links between indoor comfort, cognitive performance, and well-being. Understanding why discomfort occurs — and how to mitigate it — begins with examining the primary thermal drivers at play.

Key Parameters Governing Thermal Comfort

Engineering literature generally identifies six parameters that define human thermal comfort. Four are environmental and directly influenced by building design:

Air temperature

Air velocity

Mean radiant temperature

Relative humidity

Two additional personal factors are outside the designer’s control:

Metabolic rate

Clothing insulation

Design strategies therefore focus on managing the environmental parameters while accommodating reasonable variations in personal preference.

Influential Design Considerations in Office Environments

Improving thermal comfort during conceptual design requires more than basic sizing formulas. Internal heat gains, cubicle layouts, electrical loads, glazing orientation, and insulation all affect temperature distribution, airflow behavior, and perceived comfort. Below are several core considerations.

1. Placement of Supply and Return Air

Inlets and outlets must account for buoyancy-driven motion — warm air tends to rise and cooler air settles. However, asymmetric duct placement can create unwanted turbulence, stagnation, or short-circuiting of cold supply air. Identifying locations that avoid draft zones and maintain gentle, uniform air motion is essential.

2. Window Orientation and Solar Load

Solar exposure varies strongly by orientation and geographic position. South-facing glazing in many locations can introduce significant heat loads at certain times of the day. Architectural shading, recessed window placement, or altered glazing ratios may reduce solar heat gain. These choices directly influence HVAC load, occupant comfort, and the cooling strategy.

3. Internal and External Insulation Characteristics

External walls and roof assemblies often behave thermally very differently from internal partitions. In top-floor spaces with poorly insulated roofs, heat can infiltrate downward into the occupied area. Conversely, well-insulated envelopes may limit desirable heat exchange. Understanding these distinctions is vital in determining supply air temperature, flow distribution, and air change rates.

4. Heat-Generating Equipment

Computers, lighting, printers, and other appliances contribute continuous heat sources. They behave as convective drivers, altering natural flow paths and creating localized temperature zones. These should be accounted for when sizing the system and determining ventilation direction.

Using Engineering Analysis to Evaluate Design Decisions

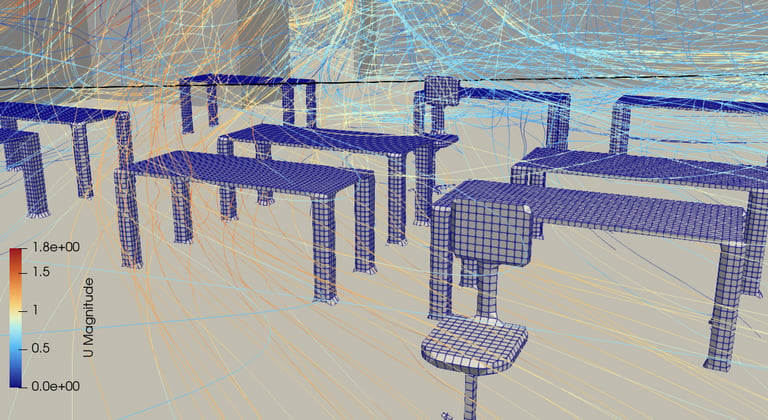

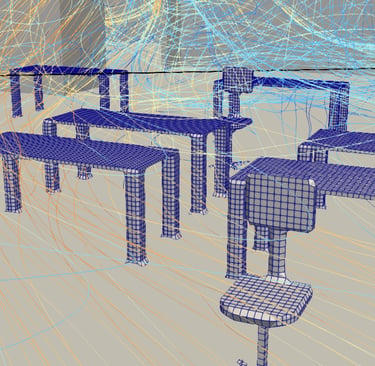

To illustrate the effect of duct placement, boundary conditions, and solar exposure, consider several example studies applied to a simplified office model on a hot summer day. The baseline space experiences 30 °C outdoor air and includes one active supply duct and one passive outlet.

Case A: Top Supply, Bottom Exhaust

Cool air enters from the ceiling and exits at floor level. This arrangement cools the space but shows moderate mixing higher in the room, slightly reducing uniformity.

Case B: Bottom Supply, Top Exhaust

Reversing supply and exhaust improves temperature distribution while maintaining adequate air motion. Air tends to sweep heat upward toward the return, creating more predictable stratification and cooler conditions near occupant level.

Case C: Heated Roof

If the office occupies an upper floor with poorly insulated roofing, significant upward heat flux can counteract the cooling pattern, producing slow temperature decay and localized warm zones. Streamline plots in such scenarios typically show warmer upward recirculation fields.

Case D: Warm External Wall

When one perimeter wall is modeled as warmer than the interior, airflow tends to sweep across the space more aggressively, occasionally improving mixing and accelerating heat removal. This demonstrates that nonuniform envelope conditions can influence air patterns in beneficial ways.

Case E: Window Facing Orientation

South-facing windows in summer months can inject enough solar load to modify circulation patterns and raise localized temperatures. A north-oriented equivalent typically shows milder thermal gradients. This difference reinforces the necessity of considering solar geometry at the outset.

What These Examples Show

Even in simplified thermal simulations:

Small variations in duct placement can influence perceived room comfort

Envelope characteristics and solar gain can intensify or suppress natural convection

Supply and return balance strongly shapes stagnation zones and flow uniformity

Boundary assumptions matter — especially in top-floor and exposed-wall configurations

Most importantly, these studies highlight that thermal design decisions should be validated early. Adjustments made after construction are costly and often constrained by existing architecture.

Designing Office HVAC Systems with Confidence

Improving comfort in workplaces requires a methodology that blends building physics, airflow modeling, material considerations, and knowledge of occupant behavior. Whether evaluating diffuser layouts, sizing equipment, testing window orientation strategies, or anticipating heat accumulation from electronics, analytical tools help reveal physical responses that cannot be captured with basic rules-of-thumb.

Early studies reduce risk, limit over-sizing, and help ensure that thermal comfort is maintained across seasons, occupant distributions, and internal loads.

Bring CFD-Level Insight Into Your HVAC Designs with tensorHVAC-Pro

If you want to explore temperature distribution, draft risk, flow stagnation, heat buildup from equipment, or the impact of envelope conditions, tensorHVAC-Pro provides a high-resolution CFD-based environment purpose-built for HVAC engineering. From office layouts to industrial halls, it helps you visualize comfort patterns, test design decisions, optimize system placement, and create energy-efficient solutions with confidence.

tensorHVAC-Pro is a dedicated HVAC flow and thermal simulation software, Intuitive and easy to use, designed for HVAC engineers - not CFD expert. Learn more..

Read more articles..